Flying into a microburst can be super scary and dangerous for any plane, even big jets! With all the stormy weather lately, there’s a bigger chance of hitting microbursts all over the U.S.

You probably remember that microbursts played a part in some big plane crashes – Eastern Airlines Flight 66 in 1975 and Delta Airlines Flight 191 in 1985.

After those accidents, we got way better at spotting microbursts, so pilots learn all about them now. But they’re still a big problem, especially at small airports without the right tools. Let’s chat about how microbursts form and where to watch out for them!

How They Form: Cumulonimbus Clouds

Research on microbursts is ongoing, but we know any cumulonimbus cloud could make one. Get this – they can happen without lightning or thunder! While microbursts come from different kinds of storms, single-cell storms are often the most dangerous. Pilots might not expect bad weather from them, so a microburst could really catch them off guard.

Why Air Goes Down: Heavy Rain

A microburst has a column of air going down super fast – we’re talking 6,000 feet per minute! Heavy rain gets it going downwards in two ways.

First, the friction between the rain and air pulls the air down. Also, dry air starts evaporating the rain. Evaporating takes energy, which it sucks out of the nearby air as heat. Basically, as the rain evaporates, it cools the air column.

The column gets denser than the air around it because cold air is heavier than warm air. So it starts dropping fast. The ongoing evaporation makes it cooler and speed up more – that’s how we get a microburst!

Wet or Dry – Both Bad News

In humid places, the microburst might still have rain when it hits the ground – those are wet microbursts.

But in dry areas like Colorado or Utah, the rain’s all evaporated before landing. That leaves an invisible column of air plunging at 6,000 feet per minute! We call those dry microbursts. You’ll see virga, then a swirly dust cloud at the bottom of the microburst.

Either way, wet or dry, they’re both super dangerous.

Spreading Out and Fading Away

When the column hits the ground, it fans out in a circle shape. At the same time, it curls inward, making a vortex ring around the edges.

Microbursts are officially less than 2.5 nautical miles wide (~4 km) with strongest winds less than 5 minutes. We just call them all “microbursts” but “downburst” includes bigger ones.

They usually peak then weaken pretty fast. One microburst is short, but they can keep hitting for 30 mins or more.

Dealing With Low-Level Wind Shear

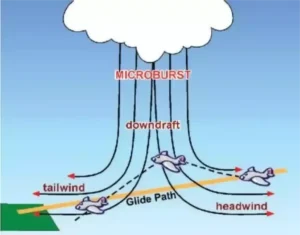

The big takeaway – all microbursts are a threat! The obvious downdraft could make you descend and hit the ground. But the huge wind shear across it can also stall you and make you drop faster.

Let me walk through an example flight path:

1) You’re going 80 knots approaching a microburst. In the vortex ring, you hit turbulence and speed up from the headwind. You start climbing since the plane handles better.

2) In the strong part of the shaft, your speed peaks at 100 knots – a 20 knot jump. You keep climbing as you hit the downdraft.

3) In the downdraft, your headwind turns into a tailwind. You sink fast towards the ground and slow down.

4) Leaving the downdraft, your tailwind surges hard. Your speed drops 20 knots to 60 knots at a high angle. You keep descending.

5) More turbulence in the last vortex. If not on the ground yet, you might climb exiting it.

Total Shear = Double the Top Wind Speed

The downdraft alone is bad news. Add wind shear, and it’s worse! If the gusts hit 25 knots, you’ll get a 50-knot change going through it – speeding up 25 knots, then slowing 50 knots.

But gusts of 45 knots mean a 90 knot shear – more than any plane can handle safely!

Dodging A Microburst

At big airports for airlines, use tools like LLWAS, TDWR or WSP to avoid microbursts if possible. ATC will warn you about wind shear there.

At smaller airports, pilot reports and your own eyes are key to missing them. Main rule is don’t fly under thunderstorms! If you see rain or virga falling with swirling dust, let other pilots know so you all stay clear.

Watch what other planes do, too. Before the Eastern 66 crash, a DC-8 reported wind shear, and another Eastern L-1011 barely made it. Even knowing that, Flight 66 kept going.

Wait It Out

Microbursts are short, with peak winds less than 5 minutes. For ones from single-cell storms you can go around or wait for it to clear out. Spotting a microburst means patience is safest – don’t fly into one! Going through or trying to land in one should be your last choice.