A yaw damper is like an automated choreographer that makes sure your flight feels smooth and steady.

This handy system takes data from sensors on the rudder and uses it to minimize fishtailing motions in single-engine planes. In jets and planes with T-tails, the yaw damper prevents uncomfortable Dutch rolling, which is a combo of yawing and rolling.

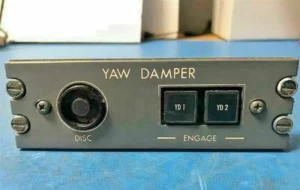

In older aircraft, the pilot could turn the yaw damper on and off. But in newer planes like the Cirrus SR22, it switches itself on at 200 feet and turns off near landing. The SR22’s fancy yaw damper talks to the avionics and ADAHRS system to keep things coordinated.

The ADAHRS keeps an eye on the plane’s every move, even when autopilot is off. If it notices an unwanted yaw, the damper uses the rudder servo to gently bring the plane back in line.

But landing with an active yaw damper takes practice. Pilots have to expertly manage the controls against the automation.

The Yaw Damper Dilemma

It’s standard in big jets to toggle the yaw damper for takeoff and landing.

Engaging it on takeoff seems logical. But if there’s an engine issue, the damper could mask clues that one engine has failed.

Landing in gusty crosswinds, some pilots leave it on thinking it’ll help. But it also limits what control inputs you can make when touching down.

The automated rudder work it does in turns is reassuring. Many pilots, even in light planes, hardly touch the pedals during turns now.

But if the yaw damper conks out, be prepared for some slips and skids. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the pilot has to manually choreograph those nice coordinated turns.