Among the array of aerobatic maneuvers, the snap roll stands out as one of the most demanding yet captivating. Often misunderstood, especially in European aerobatic circles where it goes by the name “flick roll,” the snap roll shares similarities with spins but diverges significantly from the conventional aileron roll. Both spins and snap rolls involve autorotation around the roll and yaw axes due to a stalled wing and a yaw input, rotating the aircraft 360 degrees. However, the key difference lies in the execution: conventional rolls rely on ailerons at a low angle of attack, while snap rolls are high-angle-of-attack maneuvers employing rudder and elevator inputs

Inside Snap Rolls

Let me share my experience with you. Vividly recalling my first encounter with a snap roll, the experience was marked by the astonishingly rapid roll rate, an immediate surge of high g-forces during the initial pitch-up, and the abrupt return to wings level. The sheer power harnessed by stalling the aircraft left a lasting impression. Over time, the snap roll has become one of my favorite maneuvers, equally thrilling with both models and full-scale aircraft. Beyond its visual spectacle, I’ve grown to admire the precision required for its execution. An inverted 45-degree down line, seamlessly transitioning with a snap and a half back to upright flight, followed by a crisply executed pull to level, encapsulates the beauty of this maneuver.

Executing snap rolls necessitates a thorough understanding of spin theory and recovery. Mastering spin recovery should precede venturing into snap rolls. Conceptually, a snap roll can be viewed as an accelerated horizontal spin. Allowing the maneuver to extend would lead the aircraft into a spin as energy dissipates.

Here’s how to initiate the initial snap rolls: start from a level line, ensuring an altitude that permits a half-loop recovery in case of a failed attempt. Choose a flight direction directly in front of you, as snap rolls impose significant stress on the model. Approach them with caution, gradually increasing entry speed as you gain experience.

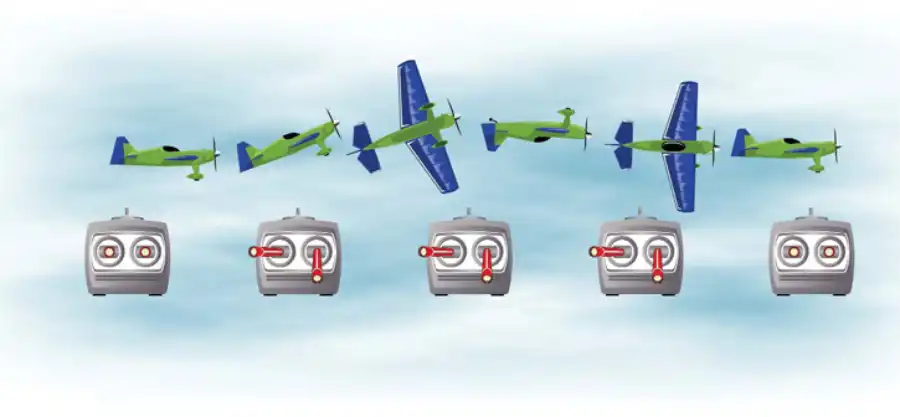

Once established on the level line, maintain cruising speed with added throttle. Simultaneously apply full up elevator and full left rudder. Torque facilitates a more responsive snap to the left. The wing stalls instantly with up elevator, inducing a yaw force similar to a spin. As the wing stalls, the nose yaws and rolls left. Sustain full left rudder and up elevator until you’re ready to halt the snap. The rapid rotation demands quick recovery, neutralizing controls approximately 45 degrees before wings level to cease autorotation. A slight down elevator may be needed to re-establish the level line, and a subtle aileron input could be necessary to stop the roll rate. Precision in stopping the roll proves challenging for most pilots, requiring dedicated practice to refine the technique for each specific model.

Some models respond better to pro-snap aileron inputs, where left aileron is applied during an upright snap roll to the left. Pilots often find improved control using pro-snap aileron if pure rudder/elevator inputs are insufficient for effective snap rolls. Experimentation with different techniques is key to optimizing the performance of your specific model.

There are several variations to snap rolls, often involving adjustments to the roll rate, whether making it faster or slower. Here are a couple of common variations:

- To increase the roll rate, many pilots incorporate pro-snap aileron (in the snap’s direction). This technique enables remarkably high roll rates.

- For a precise snap roll termination, many pilots commence recovery at about the second knife-edge position, concluding the rolling motion with aileron input. Although considered by some as a form of “cheating,” using ailerons allows for a more exact end to the maneuver. Ultimately, if judges perceive it as a snap, then it qualifies as such.

- Another method to accelerate the snap involves slightly reducing elevator input after the snap initiation. This unloads the wings, creating a higher roll rate while still in a stalled state.

- Some pilots utilize extremely high elevator throws to decrease the roll rate. By implementing these throws after the snap initiation, the model enters a deep stall, slowing down the roll rate. However, this technique may result in significant deceleration, giving the appearance of wallowing. Excessive snapping depth can lead to challenging recoveries.

- While the outlined technique focuses on left rudder for snap rolls, it’s essential to practice and master snap rolls in both left and right directions.

Outside Snap Rolls

Outside snap rolls adhere to the same fundamental aerodynamic principles as their inside counterparts. When embarking on learning outside snaps, I suggest initiating from an inverted level line and recovering to the same inverted line to minimize orientation challenges. Proficiency in inverted flight and aileron rolls is advisable before progressing to outside snap rolls. Until you feel at ease with them, I recommend performing outside snap rolls at a respectable altitude to avoid the potential development of an inverted spin.

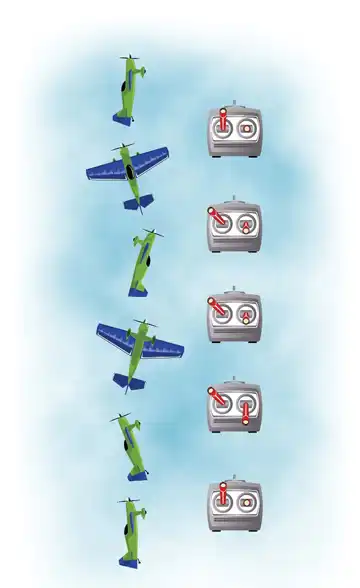

From a level inverted line, employ full down elevator and right rudder. Yes, down elevator and right rudder. Down elevator induces a stall with a negative angle of attack, while right rudder prompts the aircraft to yaw right. However, due to the inverted orientation, it gives the illusion of yawing and rolling left. Confirm this by holding your hand up for a visual aid. Outside snaps (and inverted spins) can be bewildering, making a small plane on a stick a valuable tool for visualizing new maneuvers.

The model will pitch nose up from the inverted position, and a conventional autorotation occurs, mirroring the inside snap roll until controls are released. Initiate recovery at approximately 45 degrees before reaching inverted wings level, possibly adjusting ailerons slightly for precise leveling. Exit the maneuver in the same inverted level line.

The variations employed in inside snap rolls can be applied to outside snap rolls by reversing the control inputs, except for aileron usage. In both cases, where we’ve rolled left (inside and outside snaps), when executing outside snap rolls to the right, use left rudder and right aileron.

As mentioned earlier, some models may not respond well to just rudder/elevator inputs, and pro-snap aileron could be more effective. For an outside snap using right rudder, pro-snap aileron entails left aileron, as the model rolls left. Many pilots find pro-snap aileron enhances control and facilitates cleaner recoveries. If your model hesitates to snap with just rudder/elevator, experimenting with pro-snap aileron might be worthwhile. Ensure practice includes both left and right outside snap rolls.

Common Mistakes for All Snap Rolls

- Inadequate or late recovery. It is not uncommon for the pilot to start the recovery too late while learning. The model can over-rotate the bank angle by as much as 90 to 180 degrees.

- Plunging the model into too deep a stall, leading to a substantial loss of energy and a sluggish recovery.

- Initiating the snap roll by applying either the rudder or the elevator first, rather than simultaneously. If the elevator is added first, the model climbs before stalling. On the other hand, if the rudder is added first, the model yaws before stalling, causing the snap roll and recovery heading to deviate from the intended direction.

Vertical Snap Rolls

Vertical snap rolls present a considerable challenge in maneuvering your model aircraft. Snap rolls inherently involve pronounced pitch and yaw movements. In level flight, these motions aid in returning to the level line. There’s a positive angle of attack before, during, and after the snap, requiring a pitch change. Simply releasing the stick to neutral after the snap generally results in an acceptable flight path exit.

Vertical snap rolls, however, differ significantly. On a well-established vertical line, the wing’s angle of attack is nearly zero. When initiating the snap, a rapid increase in the angle of attack is crucial to induce the stall and subsequent snap. While centering the stick stops the snap roll during recovery, it doesn’t re-establish the vertical line. The model can deviate up to 15 degrees or more from vertical, necessitating a corrective pitch input beyond neutral stick for realignment.

My approach to flying a vertical snap roll involves initiating the snap on a vertical line and accelerating it by reducing the elevator input halfway through the initial rotation for a full one-turn snap roll. Beginning the recovery at the 3/4-roll position with a sharp pitch down and neutral rudder effectively halts the snap roll. Adding aileron completes the last 1/4 roll. Some may dub this technique as “cheating,” but if it looks like a duck and behaves like a duck, it’s a duck.

Vertical snap rolls demand a significant increase in energy compared to vertical aileron rolls. The stalling wing during snap rolls dissipates substantial energy. Entry speed and the overall total energy of the model must be much higher for a vertical snap than for a vertical aileron roll.

Lastly, executing a vertical up line with a snap poses a high risk of transitioning into a spin if not executed properly. The combination of snapping autorotation, high thrust setting, gyroscopic forces, and low airspeed creates a probable stall/spin scenario. Be prepared to close the throttle and initiate recovery.

Conclusion

I encourage you to dedicate some time during your next flying session to experimenting with snap rolls. Not only do they enhance the visual appeal, but they also introduce a new dimension to your aerobatic repertoire. Although executing snap rolls cleanly is challenging, the confidence gained in handling stalls is invaluable. The ability to perform snap rolls and spins significantly boosts your comfort level, transforming stalled flight from a potential accident into a controlled maneuver. Until next time, remember that aerobatics make the world go round.