Hey there! Let’s talk about the Messerschmitt Bf 109, also known as the Me 109. This bad boy was Germany’s main single-seater fighter plane during World War II (1939-45). It was produced in huge numbers and gave the RAF’s Spitfire a run for its money during the Battle of Britain. You could find these planes zipping around all over the place, from North Africa to Russia.

So, picture this: It’s the mid-1930s, and the German government is on the hunt for the perfect fighter plane. Enter Wilhelm “Willy” Messerschmitt with his second monoplane creation. The “Bf” in the name? That’s from Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, where Willy was the head honcho of design. His Me 109 beat out some stiff competition from big names like Arado, Focke-Wulf, and Heinkel. The first prototypes were actually rocking British Rolls-Royce engines and wowed everyone during trials in Augsburg in September 1935. Later models switched to German-made Junkers Jumo 210A engines.

The plane made its public debut at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, and by 1937, it was ready for action. As Germany geared up for war, Willy took over Bayerische Flugzeugwerke in July 1938, rebranding it as Messerschmitt AG. By September, they’d churned out about 600 fighters. Some early birds got the fancy Daimler-Benz engine, which became standard by 1939. By year’s end, the Luftwaffe had a sweet collection of around 2,000 Me 109s. They were cranking out over 150 of these babies each month by 1940. Throughout the war, they kept tweaking and improving the design, eventually producing a whopping 35,000 Me 109s.

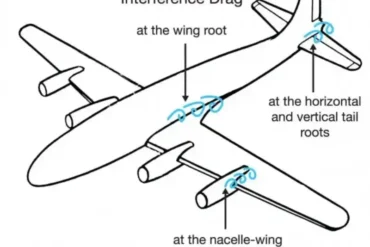

Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty. The Me 109 was a compact fighter, measuring 9.02 meters (29 feet 7 inches) long with a wingspan of 9.92 meters (32 feet 6.5 inches). It was powered by a beastly Daimler-Benz DB 605 AM 12-cylinder engine, pumping out 1,475 horsepower. Later versions got even more oomph. This little speedster could hit about 610 km/h (385 mph) and climb up to 11,550 meters (37,895 feet). There was even a special high-altitude version, the Bf 109H, that could reach a mind-blowing 14,480 meters (47,500 feet)! It could fly about 600 km (370 miles) on a single tank, but with an extra fuel tank, it could stretch that to 1,000 km (620 miles). During the Battle of Britain, the Me 109E was the Luftwaffe’s only single-seater fighter in the game.

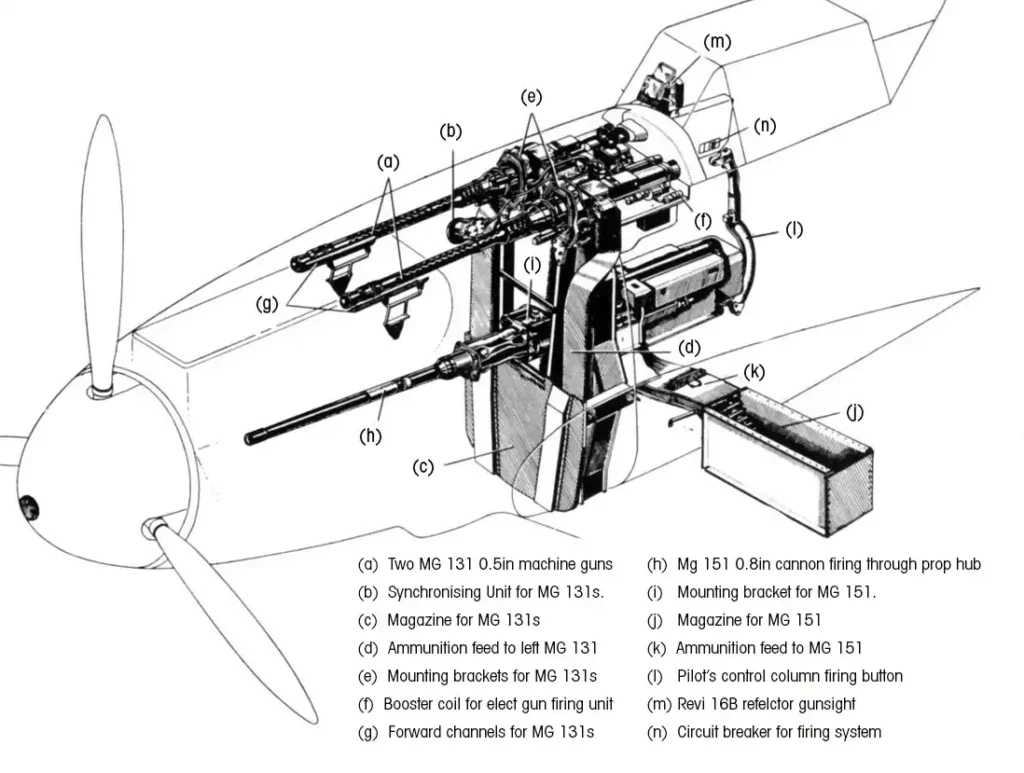

When it came to firepower, the Me 109 wasn’t messing around. It packed a cannon firing through the propeller shaft and two machine guns above the engine. The cannons ranged from 20mm to 30mm, and the machine guns were 13mm MG 131s. At first, they carried 500 rounds each, but later versions doubled that to 1,000 rounds. This gave the Me 109 a serious edge over the Spitfire in terms of firing time. A Spitfire pilot could only unleash hell for about 15 seconds, while a Me 109 pilot could keep at it for up to 55 seconds! The cannon, with its 60 rounds, could be fired separately from the machine guns, dealing some serious damage. If that wasn’t enough, they could slap on extra cannons under each wing and even carry up to 250 kg (551 lb) of bombs. Talk about versatile!

These planes were real chameleons when it came to camouflage. In Europe, they sported light undercarriages with dark green or mottled grey tops. Desert operations? Slap on some yellow paint with dark spots. Fighting in Scandinavia? Paint it mostly white. During the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940, many Me 109s rocked yellow engine covers, tail tips, and wing tips to help their buddies spot them in the chaos of battle.

The Me 109s, lovingly dubbed “Emils” by their pilots, were quick to join the action when World War II kicked off. They played a crucial role in Germany’s blitzkrieg tactics, swiftly conquering European territories. Once the dust settled, these fighters had a bunch of jobs: establishing air superiority within 50 km (30 mi) of the front lines, protecting bomber formations, defending important stuff like factories, and occasionally bombing radar stations when fitted with bombs. When the Luftwaffe set up shop at new airfields in northern France and Belgium, Me 109s could finally provide cover for bomber missions over Britain. The Me 109E was the only single-seater fighter the Luftwaffe had during the Battle of Britain. It was a close fight that turned into a war of attrition. At first, the Me 109 had the upper hand against the RAF’s top fighters, especially above 6,000 meters (20,000 feet) where it could climb faster, fly higher, pack more punch, and dive better.

The Me 109 was faster and more agile than the RAF’s most common fighter, the Hawker Hurricane. But the RAF’s ace up its sleeve, the Supermarine Spitfire, was a worthy opponent after some upgrades. The Spitfire probably had better overall maneuverability and stability, while the Me 109 had an edge with its fuel injection system, letting pilots dive without worrying about stalling. Of course, a lot depended on the skills of individual pilots. Spitfire pilots had better visibility thanks to their clear canopy, while Me 109 pilots had to deal with chunky metal framing blocking their view. German pilots quickly figured out that attacking enemy bomber formations head-on worked best.

The German pilots had some clever tactics up their sleeves. They flew in a formation called the “Rotte” with two planes about 180 meters (200 yards) apart. The wingman’s job was to watch the leader’s back while the leader navigated and protected the wingman. This evolved into the “Schwarme” where two pairs of fighters always worked together. The four planes were spread out, making them harder to spot than the tight RAF formations. Pilots who shot down a bunch of enemy planes became aces or “Experten,” earning some sweet medals. As the Battle of Britain wound down, Me 109s were reassigned to bomb London.

Even though the Luftwaffe had better formations and their Me 109 pilots were more successful than their British counterparts, a mix of factors kept the RAF from being defeated. These included the Brits’ effective use of radar, constant tech upgrades by the RAF, limited time over Britain for German fighters, and ongoing losses in bombers and fighters that couldn’t be quickly replaced from France and Belgium (since repair facilities were only in Germany). In the end, the German bigwigs switched to heavy night bombing, and the RAF came out on top in the Battle of Britain.

Me 109 pilots didn’t just tangle with enemy fighters; they also had to take down enemy bombers as the air war became all about massive bombing raids. Luftwaffe pilots figured out that attacking bomber formations from the front worked best. This tactic messed up the bombers’ formation and gave enemy fighters less time to interfere. But it wasn’t without its risks, as Luftwaffe ace Major Werner Schröer explained: “Later on we tried to attack from the front, but you could only use experienced fighters for that because of the difficulty in escaping afterwards through the formation, because you had very little time to shoot, hit him and then escape.”

The Me 109s were crucial to Germany’s Afrika Korps success in North Africa. They worked hand in hand with the German army, providing cover for bombers like the Junkers 88 that targeted British forces and defending German positions against British bombers. However, on the Eastern Front, Me 109s and the Luftwaffe in general had a tougher time. Soviet pilots and equipment kept getting better, and their sheer numbers started to make a difference. The vast distances on the Eastern Front were also a challenge for a fighter not known for its long-range capabilities, even with extra fuel tanks.

Another big job for Me 109s was defending Germany, especially against massive bomber raids by the RAF and US Air Force targeting factories and major cities. To counter these attacks, which sometimes involved 1,000-bomber raids, the Luftwaffe had to get creative. They started with the Kammhuber Line and Raumnachtjagd systems in mid-1940, where a single fighter patrolled a “box” in an imaginary grid across Northern Europe. These fighters circled in their boxes at night until radar operators pointed them towards enemy planes. This worked well until the RAF figured out how to mess with German radar during Operation Gomorrah (the Hamburg raid in summer 1943). Then they came up with “Wilde Sau” (“Wild Boar”), letting fighters freely patrol above cities and attack bombers at will. To avoid friendly fire from anti-aircraft guns, they flew above a certain altitude. “Wilde Sau” was pretty effective since Allied bombers were easy to spot from above, silhouetted against the fires they were causing below.

As the war went on, the Me 109 started to show its age. The Luftwaffe’s Focke-Wulf 190, introduced in 1942, was a step up, and the US Air Force’s P-51 Mustang was even better, with superior speed, range, and altitude capabilities. Like on the Eastern Front, America’s ability to outnumber and replace losses meant the Luftwaffe lost control of the skies over Western and Central Europe.

In the war’s final year, the Me 109 was overshadowed by the new jet-powered fighters, including the Messerschmitt 262. Hitler initially messed up by using the 262 as a bomber, only realizing his mistake when it was too late. Fighter warfare was about to change forever, with the Me 109 playing a huge role in the war and paving the way for the jet fighters that would define the Cold War era. Pretty cool stuff, right?